The incredible case really has to be explored to be believed.

I feel like we know an awful lot about the history of the human species, but that doesn’t mean a few surprises don’t come along.

Over the years, we’ve learned so much about the human’s closest relative – the Neanderthals – providing interesting results in the process.

A lot less is known about the Denisovans, another close relative who lived in the Lower and Middle Paleolithic ages.

This sub-species of archaic humans played a crucial role in the evolution of humans as we know them today, and that’s knowledge without having much information on them.

In fact, Denisovans are actually a lot more closely linked to our ancestors than you might ever think.

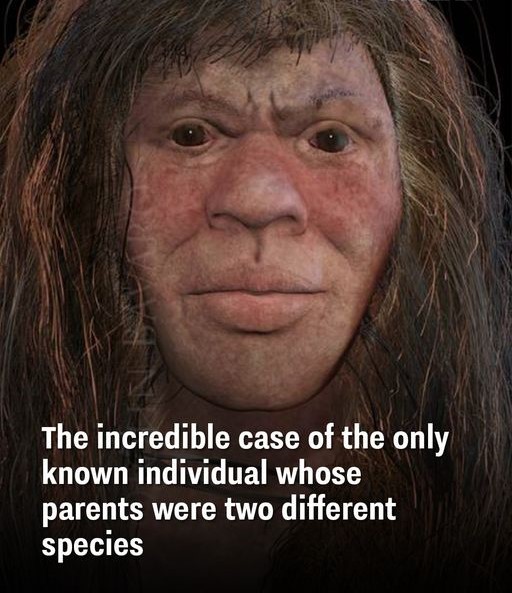

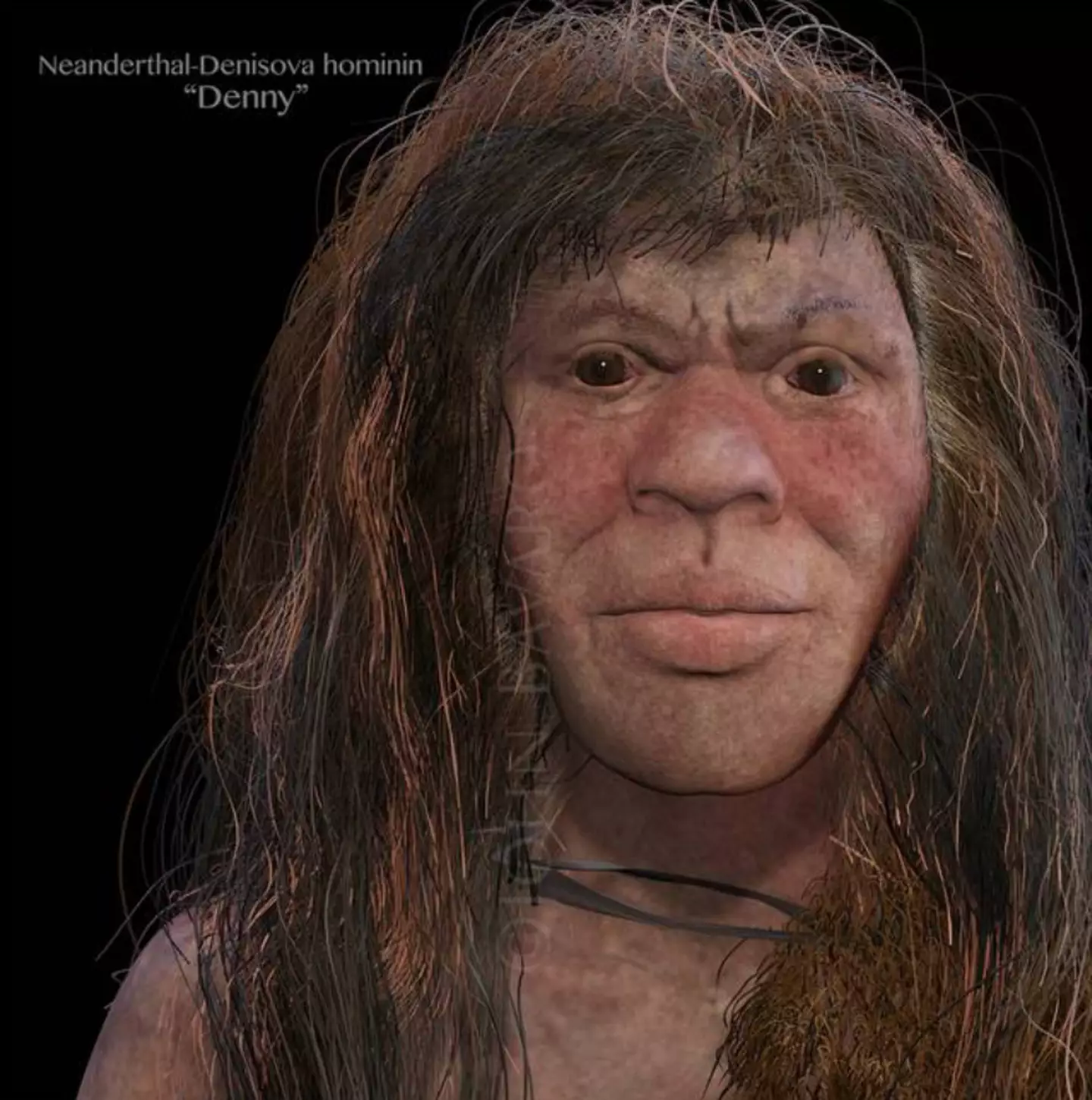

Tiny bone and teeth fragments discovered two years ago in the Altai Mountains of Siberia revealed that the only known individual whose parents were from different species.

And you guessed it… both Neanderthal and Denisovan.

The research came after a project called Finder, Fossil Fingerprinting and Identification of New Denisovan Remains from Pleistocene Asia, aimed to shed some light on the long-extinct species and their relations with both the Neaderthals and Homo sapiens.

It really is an incredible case. (John Bavaro)

Project leader Katerina Douka, of the Max Planck Institute in Jena, Germany and a visitor at Oxford University, said in a statement back in 2018: “We aim to find out where they lived, when they came into contact with modern humans – and why they went extinct.”

The team studied the bone fragments discovered in the Siberian cave in 2010, noting how nearly all of the bones had been chewed by hyenas and other animals, making them unidentifiable.

While prevailing techniques for identifying bone fragments take too long, Douka and Tom Higham – deputy director of Oxford University’s Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit and an adviser to Finder – opted for a new technology called Zooarchaeology by mass spectrometry, which capitalises on the fact that every major mammal group has a distinct form of collagen.

One of the thousands of bones studied turned out to be from a human species – which specific species, however, was not clear.

A sample was taken to Svante Pääbo at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig for more detailed analysis, which found the bone belonged to someone who was aged 13 or older at death.

A team at the University of Oxford worked on the project. (Thomas Higham/University of Oxford)

Delving in further, the Leipzig team found that exactly half of the sample contained Neanderthal DNA, and the other half Denisovan DNA.

Re-testing confirmed what the team suspected, confirming that the 90,000-year-old remains were of a hybrid daughter of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father and nicknaming the girl, Denny.

“If you had asked me beforehand, I would have said we will never find this, it is like finding a needle in a haystack,” Pääbo said.

The team’s research was eventually published in the journal Nature in August 2018, explaining: “Neanderthals and Denisovans are extinct groups of hominins that separated from each other more than 390,000 years ago.”

Leave a Reply